I was recently invited to the press opening of

Robert Lepage's "The Far Side of the Moon" at the

American Repertory Theater. Desperate as I am for magic, and desperate as I

also am to help my children to appreciate a desperation for magic (or something close to that), I took my youngest one along ... not knowing the degree to which the thing unfolds with a kind of elegant, exquisite desperation of its own.

Desperately innovative.

Desperately poignant.

Desperately symbolic.

And desperately beyond her.

Theater can do such magic. I'm so sorry I'm so rarely in its grip.

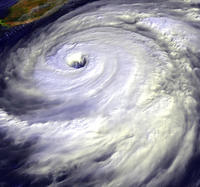

This is a virtuosic one-man show with Yves Jacques playing two brothers, both desperate, really ... one a gay weatherman in love with money, the other a kind of sweet, depressed misfit obsessed since childhood with the space race. And he is constantly, constantly failing at everything. He's really not able to connect with other humans, and his only success is a sad home-made video of his own tiny, luckless world. The video wins a contest and is chosen to be sent into space.

He deeply loved his mother, who ages and dies (it's discovered later that she killed herself), and in one scene he

becomes her ... with green pumps and a dress ... dancing slowly and lovingly with a small, alarmingly expressive three-foot-tall astronaut-doll.

Effects through projection and trompe l'oeil took my breath away. I remember feeling physically excited by their elegance and cleverness.

The final scene used the enormous mirror that had tilted and twisted to astonishing effect throughout the play. In the end it took on an angle which allowed the actor to writhe around the floor of the set and perfectly,

perfectly! create another reality in the mirror. There he was -- floating, weightless, without gravity ... slow somersaults and exquisite tumbles ... and he was perfect. A contented astronaut finally in his element.

The first movement of the "Moonlight Sonata" accompanied his floating, and it worked amazingly well.

In fact, I imagine I'll never hear those triplets in the same way again.

All of it was a gorgeous thing. I was feeling that I understood every decision ... every symbol ... every delicious metaphor for life and its absurdity. Every bit of humor was marvelous.

I wanted to kiss the actor.

At the end the theater was up on its feet, and I asked my 12-year-old if

she liked it ...

And she said she really didn't like it at all.

Of course she didn't. How could she?

She found it strange.

But it had an effect ...

The other night she told me that she's writing a short story at school about a daughter and father who discover, when rummaging through the basement, that the mother had killed herself.

(I can imagine what her teachers are thinking.)

And so up again sprang a recurrent little distance-of-mothers theme that just keeps knocking inside me. Being the reader for Earl Kim's piece "Dear Linda" the other day didn't help to make it go away, either.

Anne Sexton's love letter to her daughter is pretty damn hard to pull off: "I'm in the middle of a flight to Saint Louis ...." "I was reading a New Yorker article that made me think of my mother" ... "I love you 40-year-old Linda" ... "I wrote unhappy, but I lived to the hilt ... you live to the hilt, too Linda ...." etc. etc.

All with hauntingly sad piano sounds and flute sounds ... and cello sounds ... percussion sounds ...

It's one thing to rehearse it in a basement practice room in Harvard Square. But put the damn thing in a large, darkened concert hall, add the strange intimacy of a microphone that gives you the odd and sexy power to make huge your most whispered voice so that it reaches the exit signs ...

Well, then the thing, even when it is at its most musically cliché, becomes a thing of power ...

When you are asked to deliver: "I too was 40 once, and with a dead mother who I needed still" ...

and then think of your own mother (dead when you were 40, of course) ...

Then it gets a little surreal.

At the end: ("x, o, x, o, x, o x, o .... Mom.") the pianist and percussionist were so understated, and my x's and o's became so small, and so big ...

The audience was so very, very quiet, that the decay of the last sounds (after "Mom") went on interminably, and my eyes grabbed onto a distant corner of the room and couldn't blink, or

see. Everyone's breathing seemed to have stopped. It was such a very big relief to lower my hands in a slow signal that the thing had ended.

Thank God.