Back to the 'sphere from God-knows-where ...

smiling about Jeremy Denk's encounter with those who

overhear him practicing Berg.There's healthy blogger-anxiety over the

New York Times article conjecturing about the health of Lorraine Hunt Lieberson.

Vilaine Fille,

Alex Ross and

Steve Smith have touched on the tension between musicians and the media.

I have moved from address to address a number of times, and I carry with me a number of boxes of books. I've neglected so many of them that should I one day fall completely out of sanity, they will, I'm sure of it, plot a brutal and breathless attack on me ... I sometimes think I've heard them whispering about it already.

I'll occasionally, to ease the ache, violate them with random openings (they must hate this).

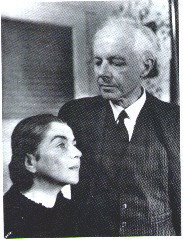

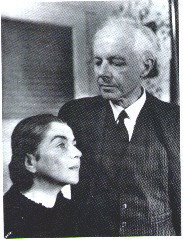

One book which I've dragged along from house to house for decades yields marvels with every violation. Written by Agatha Fassett, it is a poetic account of Béla Bartók's American years -- the last five of his life.

The Naked Face of Genius is a 1958 publication of Houghton Mifflin:

These last five years, as they slowly unfolded before me, attained in an unrelenting cycle the roundness of a lifetime, as massive and preordained as a Greek tragedy. And his wife Ditta, linked in the same chain of circumstances, inevitably shared in her own way the anguish of Bartók's destiny.

Bartók remained permanently lonely here, since he was not the kind to transplant well, and every step was made harder -- for although he did not know it, soon after he arrived here the seed of his fatal illness, leukemia, was within him, and wherever he went he was followed by the doom of his tightly numbered years.She remembes Bartók's description of his first public appearance as a nine-year-old pianist:

"It seems to me that I always played the piano, and always seriously ... that I always dug up fragments of music I considered my own; and it was never anything else but an intensely consuming occupation ...

"What I remember most distinctly from that occasion is the awareness I had of being confined within certain uncomfortable boundaries, and how I tried to console myself with the thought that this was just a temporary condition, an obstacle caused by my limited knowledge, and that it only rested within myself to break through these boundaries into a greater freedom. And the desire to do so filled me with an impatience so unbearable that it was almost physical pain.

"Nothing could speak more eloquently of my innocence at this time than the belief that I could make my boundaries disappear. For only much later comes the discovery that one remains confined, to a lesser or greater degree, forever, and the wings of one's conception are always clipped."

Fassett remembers her walks with Bartók through the Vermont countryside. He would poke at cow dung, digging into it with his walking stick:

"There is life in this dried-up mound of dung," Bartók would say. "There is life feeding on this dead heap." And he would crumble it apart with his cane. "You see," he would say, scrutinizing it intently, "how the worms and bugs are working busily helping themselves to whatever the need, making little tunnels and passages, and then soil enters, bringing with it stray seeds. Soon pale shoots of grass will appear, and life will complete its cycle, teeming within this lump of death. Once in a mound like this I found a tiny shoot of an apple tree growing, springing up with so much confidence -- a long time ago, in Hungary. It could be bearing fruit by now, but more likely its life was crushed out almost as soon as it started, for Nature takes life as abundantly as she gives it." The author tells story after impossibly poignant story, with genuine, tactile detail:

... Bartók, huddled in his old flannel robe, reminded me of a chestnut vendor bending over his tiny stove. He would be working on his Romanian collection, spread all around the room, and he needed only a glance at these single pages to place each one on the pile where it belonged. Every featherlike sheet added still one more link to the complicated system of classification, where every small variation of rhythmical pattern played a part in revealing relationships between peoples and places.

Perhaps for Bartók these notes, like pressed flowers in an album, still retained traces of their original fragrance, potent enough to draw him back to the land where he first found them and releasing him from the shadows of the room where he sat.

The story of Bartók and Ditta playing with Fritz Reiner and the New York Philharmonic is astonishing. The first performance of the Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra is described by the author who, from the audience, sensed that Bartók suddenly somehow broke away from the rest of the musicians onstage ... he was playing something entirely unknown to her, "something that had an immediate and bright existence of its own but still seemed an integral part, inseparable from the rest."

She remembers the conductor's reaction after the performance:

"What on earth came over you, Béla?" Reiner said in a voice that was cold, but somehow compassionate too. "How could you endanger everything, risking disaster for a momentary whim? Didn't you realize what an impossible task it was, trying to follow you through your wanderings? For all of us, not to mention Ditta!"

Bartók looked up at Reiner and did not say anything, and seemed to remain detached and undisturbed.

He held his brooding silence in the taxi on the way to Riverdale, and we were already going up the hill when he sat up straight and turned to Ditta.

"The tympanist," he said, "the tympanist is the one who started everything. He played a wrong note, suddenly giving me an idea that I had to try out, and follow through all the way, right then. I could not help it -- there was nothing else for me to do." I'll either hyperventilate, or read the whole thing ... Look, I've gone and typed a good chunk of it already ...