Ned Rorem's letter paints a dismal scenario of highly practiced, empty-minded virtuosos playing to score points with incurious audiences. Both are apathetic toward the new. Both have a disdain for the relevant. And they have developed a comfortable distance from the exuberance and freedom that comes with the intriguing shock of the unfamiliar.

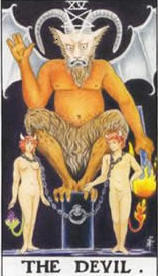

The complaint is complicated. It begins with the problem of selling. Marketing music can mean working in the Devil's workshop, or at least setting up office just a couple of dangerous doors away.

The ongoing and furious experiment of using irrelevant visuals to lure a profitable number of ears is not working. While there is great fantasy and possibility in the visual realm, and while that realm is now astonishingly easy to pass on to thousands of people, the thing being marketed is not a thing meant for seeing. It's a thing meant for hearing.

In radio broadcasting, there are often stories of really marvelous intersections of the visual and the aural realms, confessed by listeners. A driver drenched in Mozart navigates a crowded city street in the fall ... a solitary soul with Messiaen in his earbuds shuffles through a snowy campus at dusk ...

The driver, stuck at a stoplight, is compelled to focus for a moment on the pulsing, longing gestures that are unfolding in the clear air of a Mozart slow movement. His eye catches the tempo of some perfect and oblivious cloud crossing silently above the chaotic throbbing of the crowd in the crosswalk ... and he has a moment of altered perception. Elevated sensibility. An inexplicable tenderness pours through him ... a feeling of oddly removed involvement -- of being human.

I would say that this is relevance.

The solitary walker, pushing through the wind, feels the brittleness of ice under his feet, and as he plods, the bright whistle of Messiaen's piano birds fills the blue air of his consciousness. His eyes scan the shapes of the naked trees and his perception of them changes ... he sees their shapes as hauntingly beautiful. He has an inexplicable sense that he and the landscape belong together.

In these cases, the listener's perception of his own, real world is dramatically altered by music.

It's not using visuals to lure the listener.

Rather, the listener has listened, and the world has changed.