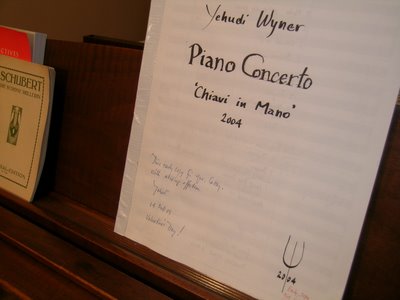

This early manuscript hasn't left my piano since it was given to me by its composer Yehudi Wyner in February 2005. It was just before pianist Robert Levin and the Boston Symphony Orchestra gave the premiere under conductor Robert Spano. I was so deeply touched, and I've lived with the score as an inspiring part of my daily landscape.

Just hours ago, it was announced that Yehudi will be awarded the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for this piece.

And I'm relishing this ecstatic feeling that the world is back to spinning as it should.

The concerto is delicious. It's charged. And it's propulsive and human .. witty, vital and warm. It glistens.

The composer's note from Schirmer:

The idea for a piano concerto for the Boston Symphony was instigated by Robert Levin, the great Mozart scholar and pianist. The idea was evidently embraced by BSO Artistic Administrator Tony Fogg and supported by Music Director James Levine.

Much of the concerto was composed during the summer of 2004 at the American Academy in Rome in a secluded studio hidden within the Academy walls. While much of the composing took place far from home, the concerto comes out as a particularly "American" piece, shot through with vernacular elements. As in many of my compositions, simple, familiar musical ideas are the starting point. A shape, a melodic fragment, a rhythm, a chord, a texture, or a sonority may ignite the appetite for exploration. How such simple insignificant things can be altered, elaborated, extended, and combined becomes the exciting challenge of composition. I also want the finished work to breathe in a natural way, to progress spontaneously, organically, moving toward a transformation of the musical substance in ways unimaginable to me when I began the journey. Transformation is the goal, with the intention of achieving an altered state of perception and exposure that I am otherwise unable to achieve.

"Chiavi in mano" - the title of the piano concerto - is the mantra used by automobile salesmen and realtors in Italy: Buy the house or the car and the keys are yours. But the more pertinent reason for the title is the fact that the piano writing is designed to fall "under the hand" and no matter how difficult it may be, it remains physically comfortable and devoid of stress. In other words: "Keys in hand."

--Yehudi Wyner, December 13, 2004

My infinite heartfelt and admiring thoughts go to this genuine and brilliant man.

There is an interview which I did with Yehudi and Robert about the concerto and much more here

Congratulations, Yehudi!

With much, much love.